By Shannon Santschi

When looking over the work and legacies of United States Supreme Court Justices Clarence Thomas and Thurgood Marshall (deceased), one would be hard-pressed to find men of more legally divergent views. But upon closer examination, it is noteworthy that these scholars have held many things in common in regards to their personal experiences, the value they placed on hard work, and their motivations as attorneys and judges. While their jurisprudence is dissimilar, both Marshall and Thomas in their respective generations, have helped advance justice and affirm individual liberties in America.

Early Influences

Clarence Thomas’ story begins June 23, 1948, in the forgotten corner of Pinpoint, Georgia, an impoverished village outside of Savannah. His parents, M.C. Thomas and Leola (Anderson) Williams spoke Gullah–a mixture of African and English languages.

When Thomas was two, his father abandoned them, and when a fire destroyed their shack, Leola moved her family to the city. In My Grandfather’s Son, Thomas writes that they’d moved from the “safety and cleanliness of rural poverty…to the foulest kind of urban squalor.” Crowded in a tenement village, raw sewage ran freely through the yard creating “a gross wetness” everywhere.

During the day, Thomas and his brother, Myers, were supposed to attend school while their mother worked, but at 6 and 7 years old, the boys were often found wandering the streets. Their truancy caught up with them, and they were sent to live with their grandparents, Myers and Christine Anderson. Thomas says the walk to the Anderson home, is “the longest and most significant journey I’ve ever made; it changed my entire life.”

In the boys’ eyes, their grandparents were rich. The refrigerator and bathtub fascinated them, but their delight was the toilet! They flushed it often for entertainment.

While Christine spoiled them with love, Myers’ Anderson was, as Thomas laughingly recalls in Created Equal, “Rules, rules, rules.” Despite being functionally illiterate, Myers was entrepreneurial and developed a business delivering oil and ice. After school, Clarence and his brother helped out. “The family farm…and unheated oil truck became my most important classrooms. It was the school in which my grandfather passed on his wisdom.”

Education, Discrimination & Revolution

Myers believed in work and did not tolerate quitters. Quitting was grounds for removal from his home. But he valued education and paid for the boys to attend Catholic school. The school was segregated, but the Irish nuns loved their students. Their demands for excellence motivated Thomas to become a top performer.

Clarence’s first thoughts of becoming an attorney came as a result of one of his grandfather’s experiences. Thomas found him drinking in the middle of the day, something he never did. A police officer had pulled Myers over for “wearing too many clothes”. The vulnerability of the experience had shaken his fiercely independent, self-made grandfather to the core.

But Thomas’ interest was in the priesthood. St. John Vianney Minor Seminary, a boarding school, was expensive and Thomas would be the sole integrating student. Myers, proud of his high-achieving grandson, agreed to pay the tuition on the condition that Clarence would not quit. Thomas fell in love with the liturgy, worked hard in school, and became the star quarterback of the football team.

His commitment to excellence was driven in part by fears of racism thus, ninety-eight percent scores were not good enough. He reasoned that if his work were perfect his teachers would have no room to deny him. Nonetheless, Thomas still felt stings of racism. When his colleagues participated in movie nights or had dinner in town, Clarence was left out as these venues were generally segregated. What was worse, none of his classmates spoke up against these injustices.

In 1968, shortly after Thomas’ arrival at Immaculate Conception Seminary, Martin Luther King, Jr. was shot. When he overheard a fellow seminarian rejoice, hoping that “the S.O.B dies”, he quit on the spot.

His decision to leave was not well received by Myers and Clarence was ‘shown the door’ that night. He moved in with his mother but later transferred to Holy Cross College in Worcester, Massachusetts. His relationship with the only father he’d known in turmoil, Thomas questioned everything, eventually embracing the works of Black revolutionaries Stokley Carmichael and Angela Davis. At the height of his frustration, he participated in a protest, which quickly devolved into a riot. Immediately, Thomas was ashamed of what he’d become. Turning to God, he prayed for forgiveness, asking him to take away his anger.

Following graduation from Holy Cross, Thomas was accepted to Yale Law School. In 1974 he graduated with a Juris Doctorate. Finding work proved to be difficult, so when Missouri Attorney General Jack Danforth’s office called, Thomas accepted.

Still holding some revolutionary ideas, Thomas was wary of working for a Republican, but he had a wife and child depending on him. As he began examining the facts of his cases, however, his views began trending to the right.

Thomas capitalized on opportunities to work at the federal level when Danforth became a U.S. Senator. In 1982, President Reagan tapped him to chair the Equal Opportunity Employment Commission. Research, debate and legislative forums were plentiful in Washington and Thomas absorbed it all. But when his grandfather died suddenly in 1988, his world fell apart. While some pleasantries had been exchanged, their differences remained unresolved. Thomas says he “wept shamelessly and uncontrollably” at the funeral.

Jurisprudence

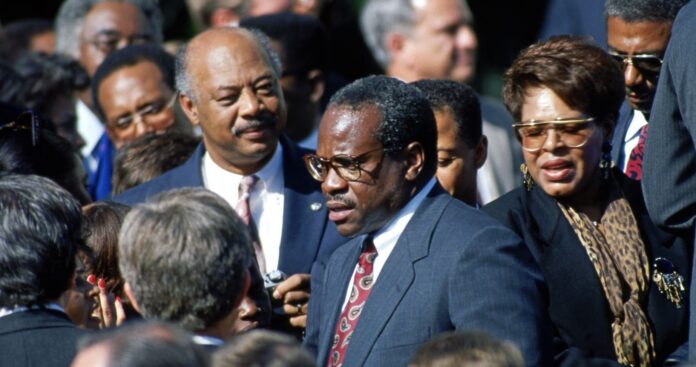

In 1991, Thomas received a call from President George H.W. Bush asking him to fill Thurgood Marshall’s seat. Following Senate confirmation hearings, which included surprise accusations by a former staffer (the FBI concluded it was an “uncorroborated story”), Clarence Thomas was confirmed and sworn in as an Associate Justice to the Supreme Court.

On the bench, Justices Antonin Scalia and Thomas enjoyed a warm friendship. Both men adhered to Constitutional originalism, but Scalia once conferred to Thomas what he considered the greatest honor, that of a “blood-thirsty originalist”.

Thomas on originalist jurisprudence:

“When interpreting the Constitution and statutes, judges should seek the original understanding of the provision’s text if the meaning of that text is not readily apparent. This approach works . . . to reduce judicial discretion and to maintain judicial impartiality. First, by tethering their analysis to the understanding to those who drafted and ratified the text, modern judges are prevented from substituting their own preferences for the Constitution. Second, it places the authority for creating the legal rules in the hands of the people and their representatives, rather than in the hands of the judiciary. . .”

With 31 years on the bench, Thomas is America’s longest-serving Justice. Additionally, he’s authored more opinions than any other justice–over 600. The legal community is attentive to these opinions, as columnist Bradford Richardson notes, that through them, Thomas “patiently plant[s] seeds that, though they ha[ve] no immediate impact, may eventually flower by the strength of their reason.”