By Shannon Santschi

Conduct a quick internet search and you will find that research and programming on financial education has skyrocketed in recent years. The trend has been global as many countries recognize that a financially literate citizenry supports the well-being of families, communities and the stability of nations.

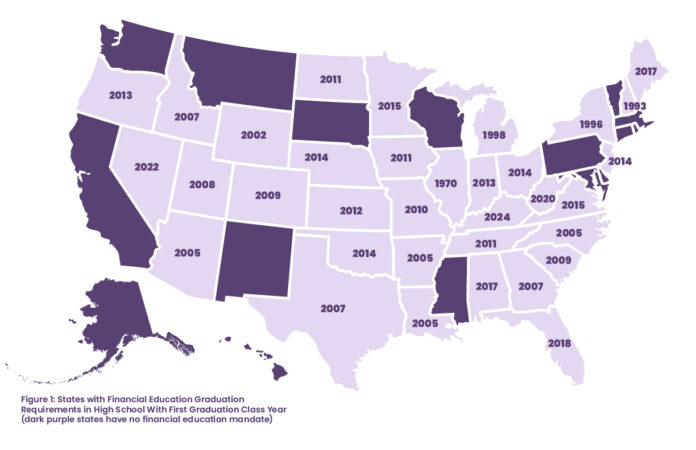

Although financial education courses have been offered in American high schools for over a century through home economic and basic math courses, in response to the Great Recession of 2008, an increasing number of states are now teaching financial education as a stand-alone course. Some are even making passage of such courses a prerequisite for graduation. And while the quality of curricula, instruction, and funding vary widely from state to state, a growing body of research is demonstrating that mandatory high-school financial education courses are having the desired effect.

Dr. Carly Urban, Associate Professor of Economics at the Montana State University, has been studying the efficacy of such programming for nearly a decade and says, “Requiring students to complete personal finance content in high school improves credit scores, reduces delinquency, reduces payday borrowing, and improves student loan borrowing decisions.” Dr. Urban’s latest research, alongside colleagues Jeremy Burke (Senior Economist, University of Southern California) and J. Michael Collins (Professor and Faculty Director, University of Wisconsin-Madison) however, has revealed some interesting findings on attitudinal differences between males and females in response to mandatory high school financial education courses.

Males and Females Differ in Response to Financial Ed Courses

Introducing a fairly new term, subjective financial well-being, a measure that “captures the extent to which people believe their financial situation provides them with financial security and the ability to achieve present and future goals”, the researchers found that in contrast to their male counterparts who feel more confident after taking a course on personal finance, overall, a required high-school financial education course seems to have no effect on women’s sense of financial well-being. Delving deeper, Dr. Urban notes that women who go on to take some college courses, do experience a positive change in their subjective financial well-being, but that “for women who end their education with a high school diploma, [a] required high school financial education actually makes them feel more pessimistic about their financial future.” This sentiment remains through age 45.

Elaborating on these findings, Dr. Urban suggests the attitudinal difference for women “may reflect that women understand the reality of their situations and are honest in their self-assessments. The education may make them realize certain goals are out of reach, but it may also make them more confident in the tools they have going forward, making it seem like there is no overall effect.”

Tying all her research together, Dr. Urban affirms, feelings aside, that “financial education is still beneficial to women: it raises their credit scores, improves their student loan borrowing decisions, and reduces their use of payday loans. The lack of change in how women feel about our financial futures says to me that financial educators should innovate to create programs that better serve women’s unique financial and labor market challenges.”

She makes the following recommendations for effective programming:

1. A good financial literacy program should touch on: budgeting, saving, investing, credit, and borrowing.

2. Programming needs to effectively reduce the risks of financial shocks, support emergency savings, and help people to manage debt.

3. Know your audience. Tailor the content. If your students are mostly college-bound, teach more content related to borrowing for postsecondary education. If your students are not planning on additional postsecondary training, learning about potential wages in different occupations, auto loans, and managing income volatility may be more important.

4. Implementing financial literacy programming for girls and young women before they begin high school may prove beneficial in a variety of ways.

While Dr. Urban agrees that a good financial literacy program should recognize and discuss “the realities of potential [financial] shocks” in preparation for the inevitable stresses of life, even in the current economic environment, parents and educators should make every effort to have “positive financial conversations rather than stressful dumps of information” from the start. “A good financial curriculum will lift everyone,” she says.

Dr. Carly Urban is an Associate Professor of Economics at Montana State University. Her research on state-mandated financial education has been informative for many state policies. She has also assisted federal agencies in interpreting financial education research, where she has been a Visiting Scholar at the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s Office of Financial Education, and at the Federal Reserve Board. Dr. Urban holds a PhD in Economics from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a B.A. in Economics and International Affairs from George Washington University.

Shannon Santschi is a contributing writer for Smart Women Smart Money Magazine. Comments or questions can be sent to staff@smartwomensmartmoney.com.