By Shannon Santschi

Janie Mines was born to William and Daisy Mines in Newberry, South Carolina, in 1958. Her family moved to Aiken, South Carolina, shortly after her birth.

At the time, Aiken was the nation’s only thermonuclear weapons fuel production facility, the Savannah River Site. Aiken’s school system served scientists’ families from all over the world, and teachers there were top-notch. Janie’s mother was a teacher and relocated her daughter to the school where she taught, which was predominantly white. Janie, curious and bright in her own right, was able to take advanced courses alongside scientists’ children.

Also the daughter of a preacher, Janie recalls either being “on the way to church, in church, leaving the church, or visiting church people.” Her younger sister Gwen was sick during the early years and rarely went outside, so Janie spent a lot of time alone as a child. Janie was never lonely, though; she’d developed a genuine relationship with her Invisible Friends–God, Jesus, and the Holy Ghost. “In her book, No Coincidences: Reflections of the First Black Female Graduate of the United States Naval Academy, she writes, “I could never be truly lonely, I always had someone I could take my problems to, and I always received wise counsel. Who could ask for more?”

Janie’s parents were encouraging and instilled in their daughters the belief that they could become anything they wanted to be. Although the family rarely talked about racism, when images on television lead Janie to question the goodness and character of her fellow African Americans, her father swiftly and lovingly addressed the issue. He shared how pictures, numbers, and words can inaccurately and unjustly influence ideas about other people, the community, and the country. Her daddy further explained that both black and white people were suffering under this scenario—blacks were being taught self-loathing, and whites were learning to fear blacks, ultimately “depriving [white people] the opportunity to know wonderful black people.”

Another lesson Janie learned came from her mother. When Janie and her sister received different gifts at Christmastime, Janie protested, remarking, “It’s not fair!” Her mother wisely informed her, “Fairness is not about being treated the same, but being treated justly. At times, treating people exactly the same is actually lazy and ineffective.”

Janie credits her childhood experiences, her Invisible Friends, and her parents for building a foundation that fostered an independent spirit and resilience—traits she would lean heavily on at the Academy.

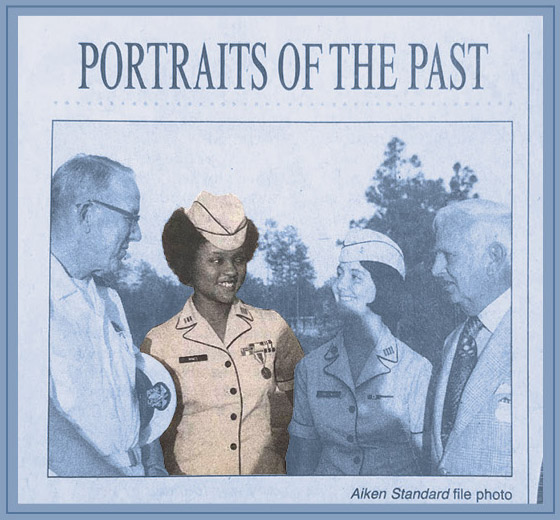

An all-American girl, Janie participated in student body leadership, academic clubs, Girl Scouts, church activities, and she earned a black belt in karate. Out of 562 students, she graduated salutatorian of her high school, an unusual occurrence in the recently integrated South.

Although she was accepted into every Ivy League university she applied to, she chose to accept the Naval Academy’s offer. Her family had a tradition of service since World War II, and Janie says, “It felt like a calling…and in terms of education, the Academy is outstanding.”

The Academy

In response to Congress mandating the inclusion of women in military academies in 1975, the Naval Academy issued the following statement, conveying their general sentiment about the change. As Janie would later realize, it was much more a warning than a greeting:

Women at Annapolis, Addendum to the US Naval Academy Catalogue, 1975-76″To sum it all up…we are planning to change very little at the Naval Academy next year. Because, first and last, like all the rest, you will be a midshipman. But it’ll probably take a little getting used to for all of us. We are looking forward to it.

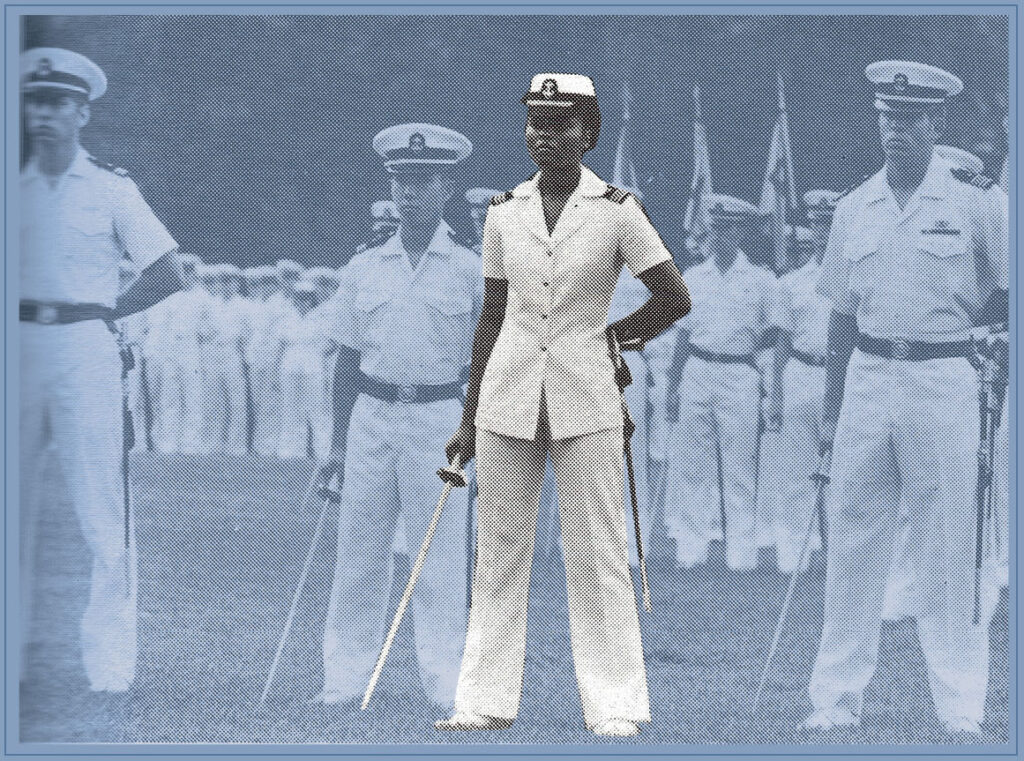

Janie arrived on campus on Tuesday, July 6, 1976. She writes, “When I first saw it, I was excited to join its ranks! I actually had no idea how unwelcome I was—and how critical my trait of independence would be to successfully navigate these treacherous waters.

The new Plebes (freshmen) were told to look at the person on their right and left. “One of you will not survive to graduation,” the man in charge said. Janie explains further: “In this line of work, failure was not an inconvenience—it was a catastrophe. And therefore, not an option.” From day one, the goal is to weed out the weak.

Janie says she understood where the Navy was coming from, though, especially since all of this was happening in the shadow of the Vietnam War. “They were admitting women into a combat school, but not allowing women to serve in combat…It was much more than a race and gender issue. They actually saw me as a threat to national security. I was told all I could do was get good white men killed…What they said was, ‘You can’t accomplish the mission. ‘What I needed to show them was, ‘Oh yes, I can! I knew I could do the job because I’d been a leader all my life. And many of the people I’d lead were white males. I loved those guys, and they loved me.

“Over the course of four years, Janie experienced discrimination and was shunned by many of her colleagues and instructors. Many infractions and violations went unreported, as the chain of command for midshipmen was often “unresponsive.” Janie also had to consider the collateral damage that could result from reporting a colleague or upperclassman.

Considering her friends and those who would follow, it was better to simply stay focused at times.

Angels and Encouragements

Even though she faced challenges regularly, there were good times, too, and she forged many friendships along the way.

In most of her classes, recognition and assistance from instructors were a “luxury.” But one professor lead by example, bringing out the best in students. Scholarly discussions and debates took place regularly, and Janie knew her voice was welcome in his class. “I wasn’t just included; I was valued,” she recalls.

In another instance, Janie suffered a badly damaged knee following a sparring match. The remedy, an innovative surgery, only made matters worse; her knee healed straight as aboard and wouldn’t bend. The result became a permanent disability. But even this did not discourage her from finishing her course.

Graduation was just around the corner, and running a timed mile was mandatory if she wanted to get that diploma. The two men in charge of timing the run told her to wait until all the others had left to get her on the track. “No one was in the field house but the three of us, and I was very awkwardly half-running and swinging my stiff leg along as fast as I could. To my surprise and delight, they started cheering for me. The pain was intense…Running was taking everything I had, but I had to try. I had to give it my all.”

Through encouragement and yelling out her time at key intervals, those men got her over the finish line at 7 minutes, 27 seconds. She’d made it with three seconds to spare. She fell on the ground a mess of tears—both from the pain and joy.

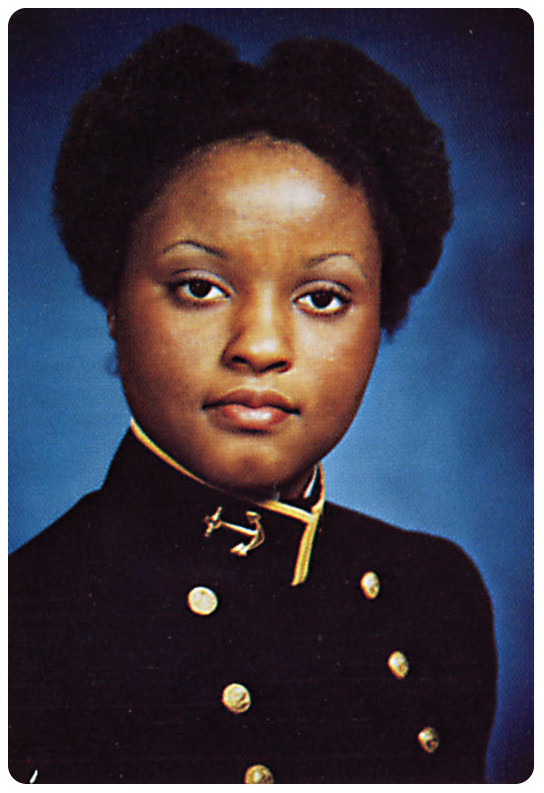

On May 28, 1980, Midshipman Mines graduated with a bachelor’s degree in General Engineering and was commissioned as an officer in the United States Navy.

Post-Military Career

After graduation, Mines earned her MBA at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology(MIT). She’s since held management positions with several Fortune 500 companies and is presently Senior Vice President at Academy Securities.

Mines, an eternal optimist, doesn’t see those who initially rejected her as foes, rather she says, “the unchallenged negative beliefs were the true enemy.” Reflecting on that time period, she says, “We grew together…I changed them, and they changed me.” She says her best friends are still her Naval Academy brothers.

She wrote No Coincidences as a “catalyst for discussion.” Her concluding message in the book is one of love and forgiveness: “We must work together to sustain our democracy.

There are those patiently awaiting its failure. I love America, and what makes us great far outweighs our ‘issues.’

Shannon Santschi is a contributing writer for Smart Women Smart Money Magazine. Comments or questions can be sent to [email protected].